Uthman

LI News Service

- Messages

- 5,513

- Reaction score

- 1,216

- Gender

- Male

- Religion

- Islam

LONDON, England (CNN) -- The world's oldest known Christian Bible goes online Monday -- but the 1,600-year-old text doesn't match the one you'll find in churches today.

Discovered in a monastery in the Sinai desert in Egypt more than 160 years ago, the handwritten Codex Sinaiticus includes two books that are not part of the official New Testament and at least seven books that are not in the Old Testament.

The New Testament books are in a different order, and include numerous handwritten corrections -- some made as much as 800 years after the texts were written, according to scholars who worked on the project of putting the Bible online. The changes range from the alteration of a single letter to the insertion of whole sentences.

And some familiar -- very important -- passages are missing, including verses dealing with the resurrection of Jesus, they said.

Juan Garces, the British Library project curator, said it should be no surprise that the ancient text is not quite the same as the modern one, since the Bible has developed and changed over the years.

"The Bible as an inspirational text has a history," he told CNN.

"There are certainly theological questions linked to this," he said. "Everybody should be encouraged to investigate for themselves."

That is part of the reason for putting the Bible online, said Garces, who is both a Biblical scholar and a computer scientist.

"Scholars will want to look very closely at it, and some of the Web site functionality is specifically for them -- the ability to search the text, the ability to highlight a word, the degree of detail is particularly interesting for scholars interested in the text," he said.

But, he added, "It's for everyone, really a wide audience, because of curiosity, because they appreciate the value of it."

By the middle of the fourth century, when the Codex Sinaiticus was written, there was wide but not complete agreement on which books should be considered authoritative for Christian communities, according to the Web site where the Codex is posted.

The Bible comes from the Monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai desert, where a scholar named Constantine Tischendorf recognized its significance in 1844 -- and promptly took part of it, Garces explained.

"Constantine Tischendorf was in search for ancient manuscripts, so he appreciated the age and value of it," Garces said.

He took a handful of pages to Germany to publish them, then returned in 1853 and in 1859 for more. On that last trip, he took 694 pages, which ended up in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The Soviet government decided to sell them in 1933 -- to raise money to buy tractors and other agricultural equipment.

The British government bought the pages for £100,000, raising half the money from the public. Garces called that event one of the first fundraising campaigns in British history.

Film footage from the time shows crowds of people turning out to see the manuscript, which was considered a national treasure, he said.

Though the Bible has been reassembled online, in the real world it remains scattered.

Most of it is in London. Eighty-six pages are held at the University Library in Leipzig, Germany, parts of 12 pages are held at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg, and 24 pages and 40 fragments remain at St. Catherine's Monastery, recovered by the monks from the northern wall of the structure in June 1975.

The manuscript contains the Christian Bible in Greek, including the oldest complete copy of the New Testament. (A copy held at the Vatican dates from about the same period.) Older copies of individual portions of the Christian Bible exist, but not as part of a complete text.

The Codex also includes much of the Old Testament that was adopted by early Greek-speaking Christians.

That portion includes books not found in the Hebrew Bible and regarded in the Protestant tradition as apocryphal, such as 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, 1 & 4 Maccabees, Wisdom and Sirach.

The New Testament portion includes the Epistle of Barnabas and The Shepherd of Hermas.

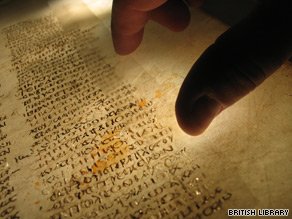

As it survives today, Codex Sinaiticus comprises just over 400 large leaves of parchment -- prepared animal skin -- each of which measures 15 inches by 13.6 inches (380 mm by 345 mm).

The British government bought most of the pages of the ancient manuscript in 1933.

Codex Sinaiticus project

Source

Discovered in a monastery in the Sinai desert in Egypt more than 160 years ago, the handwritten Codex Sinaiticus includes two books that are not part of the official New Testament and at least seven books that are not in the Old Testament.

The New Testament books are in a different order, and include numerous handwritten corrections -- some made as much as 800 years after the texts were written, according to scholars who worked on the project of putting the Bible online. The changes range from the alteration of a single letter to the insertion of whole sentences.

And some familiar -- very important -- passages are missing, including verses dealing with the resurrection of Jesus, they said.

Juan Garces, the British Library project curator, said it should be no surprise that the ancient text is not quite the same as the modern one, since the Bible has developed and changed over the years.

"The Bible as an inspirational text has a history," he told CNN.

"There are certainly theological questions linked to this," he said. "Everybody should be encouraged to investigate for themselves."

That is part of the reason for putting the Bible online, said Garces, who is both a Biblical scholar and a computer scientist.

"Scholars will want to look very closely at it, and some of the Web site functionality is specifically for them -- the ability to search the text, the ability to highlight a word, the degree of detail is particularly interesting for scholars interested in the text," he said.

But, he added, "It's for everyone, really a wide audience, because of curiosity, because they appreciate the value of it."

By the middle of the fourth century, when the Codex Sinaiticus was written, there was wide but not complete agreement on which books should be considered authoritative for Christian communities, according to the Web site where the Codex is posted.

The Bible comes from the Monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai desert, where a scholar named Constantine Tischendorf recognized its significance in 1844 -- and promptly took part of it, Garces explained.

"Constantine Tischendorf was in search for ancient manuscripts, so he appreciated the age and value of it," Garces said.

He took a handful of pages to Germany to publish them, then returned in 1853 and in 1859 for more. On that last trip, he took 694 pages, which ended up in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The Soviet government decided to sell them in 1933 -- to raise money to buy tractors and other agricultural equipment.

The British government bought the pages for £100,000, raising half the money from the public. Garces called that event one of the first fundraising campaigns in British history.

Film footage from the time shows crowds of people turning out to see the manuscript, which was considered a national treasure, he said.

Though the Bible has been reassembled online, in the real world it remains scattered.

Most of it is in London. Eighty-six pages are held at the University Library in Leipzig, Germany, parts of 12 pages are held at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg, and 24 pages and 40 fragments remain at St. Catherine's Monastery, recovered by the monks from the northern wall of the structure in June 1975.

The manuscript contains the Christian Bible in Greek, including the oldest complete copy of the New Testament. (A copy held at the Vatican dates from about the same period.) Older copies of individual portions of the Christian Bible exist, but not as part of a complete text.

The Codex also includes much of the Old Testament that was adopted by early Greek-speaking Christians.

That portion includes books not found in the Hebrew Bible and regarded in the Protestant tradition as apocryphal, such as 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, 1 & 4 Maccabees, Wisdom and Sirach.

The New Testament portion includes the Epistle of Barnabas and The Shepherd of Hermas.

As it survives today, Codex Sinaiticus comprises just over 400 large leaves of parchment -- prepared animal skin -- each of which measures 15 inches by 13.6 inches (380 mm by 345 mm).

The British government bought most of the pages of the ancient manuscript in 1933.

Codex Sinaiticus project

Source